In the light of Britain’s government’s recent vote to commence air trikes on Syria I reflected on social media that I believe petitions, emails, letters and tweets do f all for peace. I am convinced that shalom activism in our daily life and in places of discomfort are all that will ever make a jot of difference. We need more activism not clicktivism.

I was challenged by some to suggest ways people could embrace this call, so what follows is a little list of responses to the vote on air strikes. Some apply particularly to churches but most apply to any and all. Feel free to suggest additional ideas or examples in the comments.

1. Mourn and grieve

Give yourself and others space to mourn the decision and grieve the inevitable consequences: loss of life, increased migration expanding the European refugee crisis, traumatised military personnel, heightened suspicion and fear, more terrorism, increased radicalisation to name a few. I have felt very sad and conflicted since the UK MPs voted. It has been uncomfortable but necessary to sit with that and grieve. I am sure more steps to the grieving process will become apparent in the months to come.

2. Dialogue

As convicted as we each may be about our position on air strikes, most of us have doubt and confusion about the best way to improve life for the innocents of Syria and beyond. It is OK to not have the answers and even in the midst of polarised views there is room for listening and dialogue. Lack of dialogue is a root cause of most conflict.

3. Avoid knee-jerk reactions

When angry, injured or ego-driven we tend to react from a place of conflict. Like the armed jets leaving for their first military campaign just one hour after the vote, we too have often already planned how to execute our reactions. This decision means that our ears are closed to alternative options and intentional listening of the other. Lack of listening is a root cause of most conflict.

4. Nurture our young people

Our young people are the most susceptible to the fear of being at war with another country and they will be thinking about the consequences for their contemporaries in Syria. Help them to ask questions and explore their own feelings and convictions. Let them know that it is OK to disagree with you and, most importantly, it is OK to disagree with their government’s decisions. Encourage them that their voice and their vote counts.

5. Be friendly

When we are being drawn into the need to search for the enemy within it is easy to become suspicious of everyone. You can live like that if you want to, but it is pretty exhausting and lonely. I saw a cartoon on social media today which said ‘I watched the news all day and then I wanted to go out and punch my Muslim neighbour on the face. But my wife stopped me and reminded me I was a Muslim. So I turned the TV off…’. We are all discipled by something. You have a choice as to what, or who that is.

An alternative posture is to live the opposite and presume that most people are inherently good and friendly. Smile at people on the street, sit next to the person least like you on the bus or train, be quick to offer your hand to help, carry a packet of cigarettes or gum so you can offer to someone next to you in the queue. It is much more life-giving and fun.

6. Do the opposite

We (whoever we are) are often made to feel afraid of those (whoever those are) who are unlike us. This is not healthy for us but it also creates a real sense of vulnerability for those who are being demonised by the latest news story. In the current climate many from a Muslim background are feeling especially scapegoated. My friend Tim and others decided to walk in the opposite direction of the contemporary narrative and the night before the Syria vote said this:

“Tonight a small group of us from church decided to spend some time in an area of Cardiff that has a large Muslim community…. With the rise in Islamophobia we wanted to let the community know that we were saddened by this and cared about them. The men gave out packets of biscuits and the girls gave Muslim women small bunches of flowers. It was pretty overwhelming to witness the response of this small gesture.

The Muslim women were so touched by the flowers. One woman came back to us and said how it had blessed her heart and asked one of our girls for a hug.”

Fears were stilled, hearts were warmed and genuine friendships were made.

7. Go the extra mile

In addition to walking in the opposite direction, shalom needs to be built across wide divides. This requires some to go the extra mile and enter places they find most discomforting. We live in a world of diversity with such potential for misunderstanding, stereotyping and conflict. Perhaps you need to be brave and go to the place you most fear – the council estate, the gay bar, the Conservative Club, the mosque, the champagne bar, the bookies, the church, the away team pub, the synagogue, the refugee camp – you may be surprised at how welcomed you are. You may even find you have some stuff in common.

8. Build common ground

If you find you do have something in common, you might find ways to organise together towards that aim and find unity within your diversity. Everyone wants peace – do something together to build towards this. Opportunities for forcing lasting change are increased when people gather together across difference and work for a shared vision of the common good. Every neighbourhood in the world needs groups like that. This is where movements begin. But it takes patience, perseverance and a commitment to work beyond your narrow self-interest. Start off with something small that you can all agree on – a local eyesore that needs sorting, broken street-lights, a dangerous road crossing that can be improved. Listen to one another and democratically agree on what you want to change.

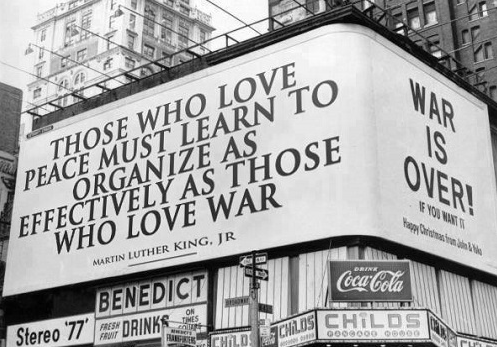

Remember, those who love peace must learn to organise as effectively as those who love war.

Love peace? Get active. Get organised.